Dr Simon E.B. Thierry (Adoc Mètis)

Adoc Mètis is a training company specialized in human resources management for the academic sector in France. Since 2013, the company provides trainings for doctoral supervisors in a dozen universities and national research institutions, as well as trainings for doctoral researchers, including trainings about research integrity (RI). In this paper, we give our feedback, as trainers of supervisors, regarding the need for training about research integrity, and present advice about how to promote research integrity towards doctoral researchers.

Adoc Mètis is a small company, with six people working as consultants, trainers and researchers. The trainings provided cover research methodology (including RI), equality & diversity, management (including doctoral supervision) and pedagogy.

This paper presents feedback from exchanges that took place during training sessions. The material used comes from exchanges with doctoral supervisors during general supervisory training that include modules on RI, from exchanges with doctoral supervisors during feedback sessions four to six months after the initial training and from exchanges with doctoral researchers during training sessions that were dedicated to RI.

The material was collected through written syntheses by the trainers after each training, and through evaluation surveys sent to the trainees a few days after the training. At one point in this article we use data from preliminary questionnaires sent to doctoral supervisors before the training.

We use data from 81 training sessions for supervisors (about 800 participants) and seven training sessions for doctoral researchers (about 100 participants) given in twenty-three different cities throughout France, between January 2020 and June 2023.

The need for research integrity training towards doctoral supervisors

If supervisees are to adopt the RI practices promoted by their supervisors, it is important that the supervisors have the resources and knowledge to do so. Let us take a look at the state of things regarding their current training and preparation.

To our knowledge, very few French institutions (universities or national research organisations) have made trainings about RI mandatory for researchers in general or doctoral supervisors in particular[1]. There is no national regulation stating that researchers should be trained in RI, except for doctoral researchers, who have been required to attend a training on research integrity and research ethics since 2016. We can therefore hope that within a few years, when those doctoral researchers have become supervisors, most supervision teams will include at least one supervisor who has attended training.

At the moment, however, the vast majority (90% to 95%) of supervisors who attend our training sessions report that they have never been trained in RI topics. They also indicate not knowing what resources are available for them, should they want to know more, even though there is a MOOC (Université de Bordeaux, 2017) in French that is recommended to doctoral researchers by most of the doctoral schools.

When doctoral supervisors indicate that they have already attended a course on RI, they generally comment that the course focused on a research fraud angle (falsification, fabrication and most of all plagiarism). The other aspects are either rarely discussed, or not remembered by the doctoral supervisors. When we broach RI, supervisors seem to discover the width of the subject and lack awareness of emerging issues such as open science. Trained supervisors also report that the trainings they attended were theoretical and that they thus lack practical advice on how to address RI with doctoral researchers. This leads to a global consensus among the participants of our trainings that when they discuss RI with their supervisees, they mostly talk about the risks of getting caught in case of malpractice.

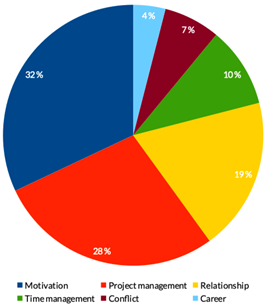

We analysed the responses to preliminary questionnaires sent to doctoral supervisors a few weeks before the training, asking them what they expected to learn during the training. 32% of the answers relate to motivation, 28% to project management, 19% to the relationship with doctoral researchers, 10% to time management, 7% to conflict management and 4% to preparation for the post-doctoral career. The results are shown in Figure 1.

In all the 605 questionnaires we analysed[2], RI was not mentioned once, even though all the questions were open-ended. Analyzing the notes taken by trainers at the beginning of each session, when we ask the trainees what their expectations are, we find that RI is very rarely mentioned during these introductions and that, when it is, it is because the corresponding supervisors have had an experience with a doctoral researcher committing fraud.

In conclusion, we believe that RI needs to be a subject of training for doctoral supervisors, either in specific training sessions or during more general trainings, for several reasons: firstly, because they don’t have many opportunities to discover and explore RI issues; secondly because they lack practical advice about how to talk about RI with the supervisees; and finally because it is not currently perceived as an important issue by doctoral supervisors…at least until they learn more about it.

Problems with research integrity training according to doctoral researchers

We analysed the notes taken by trainers after RI training sessions of doctoral researchers, and after training sessions about other subjects in which we discuss RI. The aim was to determine what they thought of RI trainings.

The clearest outcome is that doctoral researchers feel that RI trainings are not in line with the day-to-day reality: they feel trapped between the pressure to publish and the RI guidelines and do not have the power to change practices even if they believe in RI.

In France, RI training has been mandatory for all doctoral researchers since 2016. When we broach RI in our training sessions, many doctoral researchers who have previously received other training on RI report that they actually learned a lot, because their previous training mainly dealt with fraud, and sometimes specifically with plagiarism. According to these doctoral researchers, the angle of the training has been ‘‘what do you risk if you get caught?’’.

This approach gives doctoral researchers the impression that they are being talked down to, as if they had an obvious inclination to malpractice and grown-ups have to warn them of what would happen. They also frequently reported the same feeling about RI presentations during general meetings of doctoral schools, which have felt like administrative information and focused on the mandatory aspect of the training rather than the reasons the trainings were put in place.

How to transmit research integrity principles according to doctoral supervisors

The material for this section consists of discussions that took place during feedback sessions, four to six months after the initial training of doctoral supervisors. During that period, they put in practice what they have learned and the feedback session allows them to discuss what works and what does not work. It is an invaluable tool for us trainers in order to know how to adapt our training and the advice we give. In this section, we detail the methods that gathered the most positive comments from the trained supervisors.

First of all, supervisors who use one-to-one discussions with their doctoral researchers seem to express more satisfaction regarding the RI practices of the supervisees than the supervisors who rely on mandatory training and/or doctoral schools. When they took time to discuss RI in private with doctoral researchers, they report interesting consequences: doctoral researchers are more interested in RI, and tend to question the practices they witness in the laboratory. Testimonies of doctoral supervisors who took this time were often triggered by expressions of frustration from other supervisors regarding RI practices, and in all cases documented in the trainers’ notes, the frustrated supervisors had relied on the institution (i.e. mandatory training) to train their supervisees.

Moreover, some supervisors mentioned an interesting side effect: discussing RI with the supervisees can raise questions that the supervisors find challenging, leading the supervisors themselves to feel like they have learned something about RI.

The second piece of advice that supervisors report as having some success is that it is important to give sense to RI principles: supervisors who ask supervisees to blindly follow the rules (e.g. ‘‘it’s always been like that’’ or ‘‘just do as you’re told’’) often express frustration at their lack of discipline, whereas those who report having explained why the RI principles exist and having given justification to the rules seem to be more satisfied with the resulting behavior of doctoral researchers.

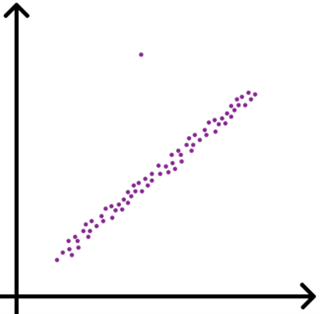

One particular supervisor gave the example of a discussion she had with her supervisee: the latter wanted to remove a data point he believed was the consequence of a measuring error (this example is illustrated by the uppermost point in Figure 2). At first, the supervisor told him that they could not do that, because if anyone found out that they had removed data, the article risked being retracted. The consequences were a discussion with the doctoral researcher about weighing the risk of getting caught. She then changed her angle and explained that humility dictated they did not remove the data point, for even if she was also convinced that it was a measuring error, there was still a chance that some time later a similar experiment might show the same strange data point, leading the scientific community to identify a rare phenomenon. After that, the doctoral researcher stopped arguing and fully agreed to submit an article with a figure showing the problematic data point and a discussion explaining why it was treated as a measuring error and thus discarded in the analysis.

Finally, both during the initial training sessions and during the feedback sessions, supervisors frequently express frustration with the evaluation system not encouraging integrity, even at the doctoral level: pressure to shorten the duration of doctorates, pressure to publish more papers during the doctorate, mandatory publication to be granted the right to defend, and evaluation of the supervisors by the number of articles co-authored with supervisees.

Conclusion

According to the discussions we have had with supervisors and with doctoral researchers during training sessions, doctoral supervisors play a central role in raising doctoral researchers’ awareness of research integrity. Doctoral researchers are rarely persuaded to change their practices by trainings or by doctoral school meetings, and one-to-one discussions allow to give sense to RI principles.

The research environment is also crucial, as convinced doctoral researchers have little power to implement good practices. But too few senior researchers are trained in matters of RI.

Systemic pressure to publish remains the main issue: doctoral researchers have to choose between quality and quantity, and doctoral supervisors feel guilty if the supervisees do not publish enough.

We recommend that training and/or resources are provided to RI trainers in universities, to enhance the quality of RI trainings. These trainers should work within a network in order to share practices and tools. For senior researchers, we also recommend finding incentives for RI training, rather than relying on mandatory training. RI should be mentioned in other training courses (e.g. management courses). Focus should be made on training heads of teams and laboratories, as training researchers in a position without power is pointless in the short term.

Last but not least, we join the chorus in recommending a reduction in the use of quantitative bibliometric indicators in research evaluation.

Resources and references

Hasgall, A., B. Saenen and L. Borrell-Damian (2019), Doctoral education in Europe today: approaches and institutional structures, EUA Council for Doctoral Education

Université de Bordeaux (2017), Intégrité scientifique dans les métiers de la recherche, France Université Numérique, https://www.fun-mooc.fr/fr/cours/integrite-scientifique-dans-les-metiers-de-la-recherche/

[1] Things are different in other European countries (see Hasgall et al. 2019, fig. 14 on page 23).

[2] Completion of the pre-training questionnaire is not mandatory. In the 81 training sessions analyzed, 605 pre-training questionnaires were sent back to us.